Literacy Lens: Four Ways States Can Implement Evidence-Based Literacy Practices

Literacy is once again in the national spotlight. Whether it’s called evidence-based literacy, science of reading, or some other nomenclature, most educators agree that schools across the country need to implement stronger literacy instruction. The 2022 scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) showed the largest decline in reading since 1990. While the pandemic certainly impacted these scores, they’d already been mostly stagnant since 2012.

To address this issue, many states have enacted new legislation, licensure requirements, and professional development initiatives aimed at aligning literacy instruction with the practices research shows to be most effective. Overhauling literacy instruction is not an easy undertaking. It requires not only broad, systemic change, but also changing the hearts and minds of educators—many of whom have strong beliefs about their instructional practices.

As a former literacy education professor, I have spent years immersed in reading research and have followed the latest iteration of the reading debate closely. While I approach these matters temperately, with an awareness of the importance of context, and a deep respect for teacher professionalism and autonomy, I am still cautiously optimistic about the national focus on reading achievement. As such, I want to share four ways states can implement evidence-based literacy programs for lasting change.

Lead With Equity

As I’ve written before, literacy can and should be interwoven with equity. There continues to be a gap on these assessments between the scores of white students and those of students of color. Similarly, students with disabilities, students in urban and rural communities, and English learner students all consistently score lower on NAEP reading tests than their privileged counterparts. All children deserve access to equitable, high-quality instruction. Thus, when we discuss these sweeping changes, we must remember to center those farthest from educational equity so that all students can be successful.

It is also imperative that literacy plans include culturally responsive practices aligned with research on the best ways to teach students from various marginalized groups. For example, while 32 states have enacted legislation that explicitly mentions English learners, few highlight findings from research conducted in the last 20 years. That research demonstrates how crucial oral language and background knowledge are for English learners—two areas that are less prominent in science of reading conversations. Consequently, as some scholars have argued, science of reading initiatives don’t always meet the needs of multilingual learners.

An effective, comprehensive literacy plan considers the needs of all learners. The following examples provide possibilities for how to thoughtfully incorporate equity into school, district, and state literacy frameworks.

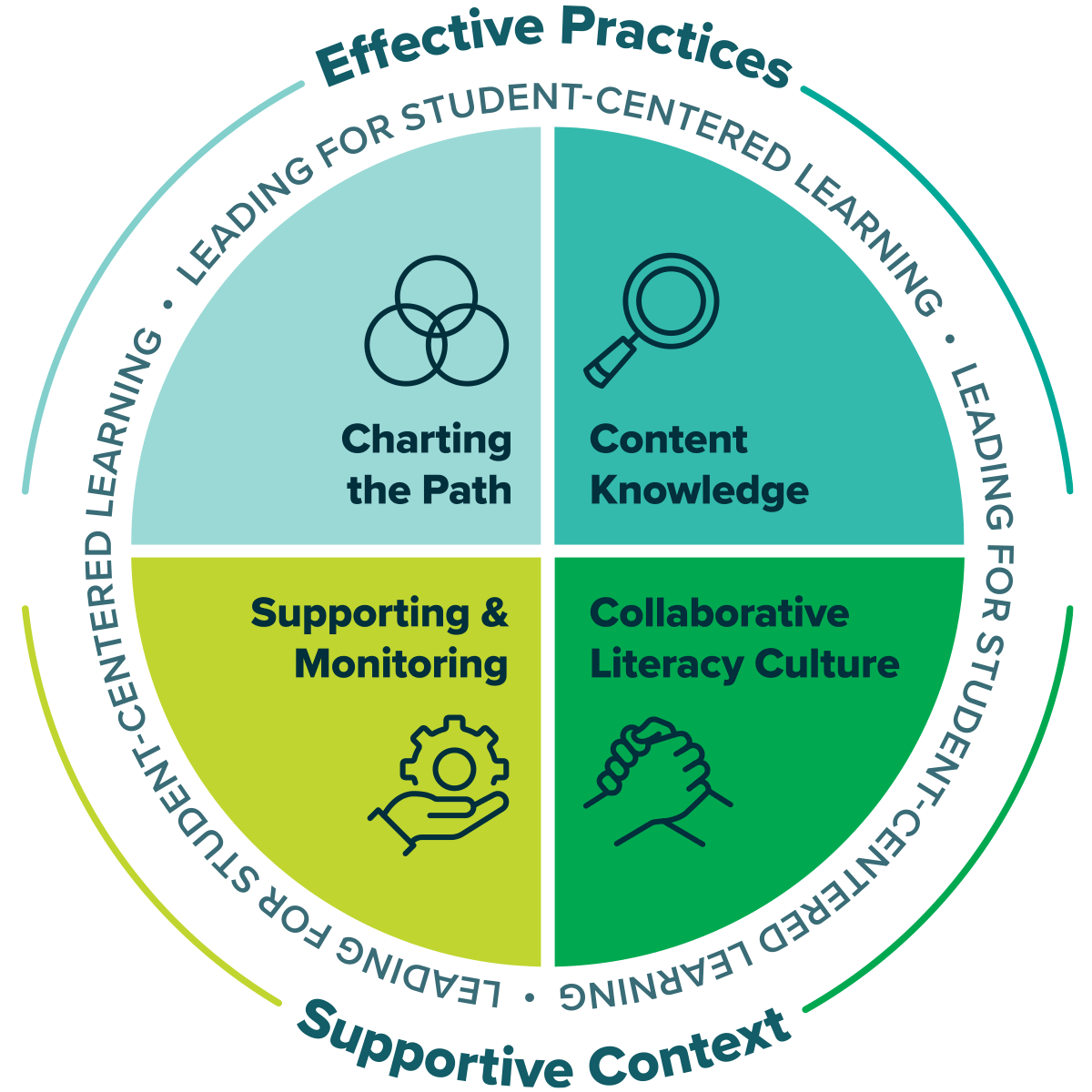

In Education Northwest’s Framework for Literacy Leadership Development, equity is explicitly called out in at least one indicator in each of its four domains:

- Charting the Path: Empower staff members to make equity-based literacy decisions to ensure inclusions and access

- Content Knowledge: Ensure practices, resources, and programs meet students’ unique language needs (e.g., multilingual learners)

- Supporting & Monitoring: Support teachers in the use of evidence-based instructional practices for all students and provide actionable feedback

- Collaborative Literacy Culture: Promote schoolwide culturally responsive practices

Likewise, Oregon’s Early Literacy Framework reflects the state’s commitment to providing equitable literacy instruction. Its first section, “Student Belonging – A Necessary Condition for Literacy Learning”, prioritizes culturally responsive practices and social and emotional learning, positioning the entire framework with an equity lens. Throughout the document, explicit attention is paid to equity—as in the section on oral language, which includes attention to multilingual learners and Indigenous languages. The framework is bookended with a final section (“Reaching All Learners”) that provides guidelines for supporting multilingual learners; students with reading difficulties, reading disabilities, and dyslexia; and talented and gifted students.

Focus on Educator Development

After parents, the person who has the greatest impact on a child’s literacy achievement is, of course, their teacher. Consequently, improving literacy instruction requires a serious investment in educator development, including funding, compensation, and incentives.

Research indicates that meaningful learning is a slow and uncertain process for teachers, resulting in varying degrees of change through participation in professional development. For change in practice to take place, teachers need time to wrestle with and apply new concepts, and, ultimately, see student results before they commit to sustaining new practices. This requires time and resources that states must be willing to invest.

States must be critical consumers when selecting training and development options. We know that the sticker on a box does not always accurately reflect the product inside. Involving educators, researchers, and administrators in the review process can help states make smart decisions about investing funds in training that truly aligns with their vision and provides educators the support they need to improve their practice. One result of such a review process might be an approved list of materials and/or vendors.

The Alaska Department of Education & Early Development approached its literacy strategic planning with a strong focus on developing teachers and school leaders and equipping them with the necessary content knowledge. In fact, the first strategy in Alaska’s Strategic Reading Plan is professional development. To that end, the department invested a great deal of time and resources in providing the following trainings:

- Alaska’s Reading Playbook Webinar Series

- Supporting Effective Literacy Instruction Class

- Alaska Science of Reading Academy for Leaders Class

- LETRS Class: Teacher, Administrators, Early Learning

- 2023 Alaska Science of Reading Symposium

- Assessment Literacy

Additionally, they’ve dedicated several webpages to literacy resources and content. Their administrators and teachers have a plethora of supports aimed at implementing strong literacy practices. They’ve positioned their educators to meet the expectations of their legislation, the Alaska Reads Act.

Utilize Implementation Science to Build Buy-In

Oregon isn’t the only state to develop a framework for literacy, and with good reason. Effective implementation of any new program or initiative requires careful, big-picture planning. The pre-implementation phase is a critical period in the implementation process. Too often in education, we skip this step and immediately begin making changes. Unfortunately, this likely contributes to the fact that most education initiatives have a two- to three-year lifespan.

Rather than building the plane as we fly it, as the saying goes, we need to have a vision, devise a plan, build the plane, and then fly it. This means taking the time to think long-term, listen to the voices of all stakeholders, and build trust and buy-in. A collaborative approach offers a greater chance that all parties will feel ownership and responsibility for the plan’s success.

Obviously, education preparation is an important component of this change process. In the pre-implementation phase of literacy reform, collaborating with partners in educator preparation is a crucial step. Again, as a former literacy professor, I’ve seen this done poorly. I’ve seen teacher education programs villainized in the science of reading debate and, subsequently, targeted with sweeping changes. As a result, many professors responded to the changes with resentment and resistance. States could avoid or minimize such reactions by truly partnering with educator preparation faculty members, school leaders, and teachers.

Even with buy-in from all partners, effective implementation requires resources. Revamping literacy methods coursework for prospective teachers and offering sufficient professional learning opportunities to retrain practicing teachers is a costly undertaking. Most states’ laws address preservice training and in-service professional development, with 25 and 32 states, respectively, discussing them in depth. However, only about a third meaningfully discuss curriculum or leadership responsibilities and most don't offer the implementation support needed to change school systems on a broad scale. If reform efforts are to be successful, states must invest in them.

Support Legislation with Adequate Resources

As I’ve mentioned throughout this post, many states have enacted legislation around reading instruction in recent years. The Shanker Institute analyzed a total of 223 bills enacted in 45 states and the District of Columbia. Unfortunately, many of these laws don’t include the necessary support to implement the new laws. For example, in some states teachers are being asked to spend outside hours in trainings without extra compensation for their time.

According to the Shanker Institute analysis,

What raises concern is the unequal focus on different student groups by states, paired with an emphasis on screening and assessment that isn't balanced with a corresponding commitment to comprehensive student supports. Similarly, teachers’ knowledge about scientifically based reading instruction isn’t enough; additional supports like effective school leadership and high-quality curriculum are indispensable for educators to apply their knowledge and achieve results with students.

Ohio recently enacted legislation around the science of reading. Wisely, they’ve also allotted funding to support the work. Funds from Ohio’s two-year operating budget will go toward implementation — $86 million for educator professional development, $64 million for curriculum and instructional materials, and $18 million for literacy coaches.

Without such supports, these laws are simply unreasonable and can only foster frustration and resentment among educators. They run the risk of encouraging a compliance mindset, in which teachers do the bare minimum necessary to give the impression of meeting requirements. Obviously, that kind of effort will not lead to the lasting change lawmakers are hoping for.

Call to Action: Create Conditions for Lasting Change

This is no easy task, but improving literacy outcomes for students is worth the effort. Below, you’ll find a list of resources to support educators and leaders in ensuring high-quality, equitable literacy education for all students.

Literacy Lens: Literacy Leadership for Positive Change

One of my previous blog posts examined the crucial role school leaders play in supporting the implementation of evidence-based literacy practices.

Evidence-Based Literacy Implementation

When schools focus on literacy, they help students lay the foundation for a successful future. Literacy skills equip young people to succeed academically in all subjects, excel in the workplace, and participate meaningfully in civic life.

Literacy Lens: The Impact of Literacy Leadership

Improving literacy outcomes for all students starts with consistently implementing evidence-based practices—and that requires strong leadership.

Literacy Lens: Data-Driven Literacy Leadership

Teachers are more likely to use new literacy initiatives they believe will help students. Principals can use data to get that critical educator buy-in.

Preparing Alaska School Leaders to Support Science of Reading Implementation

In spring and summer 2022, the Alaska Department of Education & Early Development partnered with Education Northwest to deliver the Alaska Science of Reading Leadership Academy. Learn more in this case brief.

Implementation and Coaching

Build your team’s confidence and capacity to transform learning. Set the conditions for students to thrive by nurturing confident, prepared, and connected educators. We coach educators at all levels to develop the capacity to transform systems, support their colleagues, and create opportunities for students.